In the very early 1900s, the State Female Normal School was a small collection of brick buildings on High Street. Behind those buildings, in the southern direction, lived a vibrant predominantly Black community. Unlike today’s campus “triangle,” streets ran through the middle of Ely Street (later renamed Griffin Boulevard) and South Main Street, lined with houses, businesses, restaurants, houses of worship and other gathering places.

"Proposed Plan for the Development of the State Female Normal School" (Top) and 2013 Aerial Image of Campus (Bottom) / Courtesy of Archives and Special Collections Librarian Jamie Krogh

Spanning the 20th century, hundreds of people were displaced from this neighborhood as college administrators and state officials repeatedly used eminent domain or threatened property owners with the practice in order to expand the campus and create the modern triangle. While the practice was used against both white and Black property owners, Longwood's use of eminent domain was particularly destructive to the surrounding Black community.

Eminent Domain is the power of government entities to forcefully purchase properties without the consent of the property owner in exchange for “just compensation.” By initiating condemnation proceedings — the legal process of eminent domain — or by threatening their usage, Longwood was able to acquire the vast majority of properties within the triangle.

Between 1911-1990 Longwood used eminent domain 11 times to purchase properties, and likely threatened property owners with the practice more commonly than that, according to a January 2025 letter from University President W. Taylor Reveley IV to members of the General Assembly, and confirmed through public records and interviews with community members.

The Families Within the Triangle

“Places just started disappearing, people just started moving, and being a child, you didn't know why they were moving,” said Jackie Reid.

Reid is a native of Prince Edward County and the daughter of Bland-Reid Funeral Home founder Warren A. Reid. She grew up within the triangle in a house her father built near Vine Street. Her mother operated a beauty parlor and barber shop where the Reid parking lot is now.

Farmville Topographic Map, 1968 / Courtesy of the United States Geological Survey

When she grew up, Redford, Chambers, Madison, Pine, Vine and Franklin Streets ran through the middle of the modern-day Longwood campus — rather than the sidewalks and lawns of Brock Commons today. According to Reid, the majority of the cross-streets between South Main Street and Ely Street were made up of Black homes.

James Ghee, another native of Prince Edward County who lived on South Street near where Macado’s sits now, spent much of his childhood with the Black community within the triangle. He was 14 years old when the Prince Edward County Board of Supervisors shut down public schools in 1959. He attended Mary E. Branch Elementary School, the segregated Black elementary school in Farmville, until he was sent to Iowa in order to get his education.

“It was an exciting community. The Elks Hall was in that community, Dean's Luncheonette was in that community. Coles’ Store was in that community,” he recalled.

Photo of Jackie Reid / Courtesy of Bland-Reid Funeral Home

Both Reid and Ghee remember the community very fondly. Reid said, “It was great, because it was close to 50-60 kids on those three blocks, we hung out,” she said. “You go out in the morning, you stayed out, came in for lunch, and went back in when it got dark.”

“In the summertime, we would ride bikes, skate, double dutch, you name it,” she said. According to her, children from the community would frequent a restaurant within the triangle. “For $1 you could get a hamburger, with lettuce and tomato for 30 cents. Hot dogs were 20 cents… You could get a scoop of ice cream for seven cents, a double scoop for 14 cents,” she said. “Even students from Longwood used to come over.”

Ghee said the children from the community would often play together. “There was this couple up on Ely Street that would be out on their side lawn playing croquet, and we could stop and play with them,” he said.

“The hill going down Redford, when it snowed… that hill was ours for sledding. All day long, sledding, because there were Black residents on both sides of that hill,” Ghee said. “That was our recreation, that was our community.”

"Young Women Picket a Store That Discriminates" in Farmville, 1963 / Courtesy of Encyclopedia Virginia

“There were people in that neighborhood who were like our parents, because everybody in that neighborhood knew who the children were and whose children they were,” Ghee said.

This neighborhood had invisible but clear borders, according to Reid. “We were segregated and you knew the social rules and stuff like that. You knew you couldn't go into Roses’ downtown and sit at the counter, or things that you knew you didn't do. But in this little area, you know anybody's parent could correct you. If they saw you hanging out, they’re going to get you, and then they’re going to tell your Mama, and she's going to get you,” Reid said.

Ghee, in his youth, delivered newspapers to the community later uprooted by Longwood’s expansion. “Because of segregation, I could only deliver the newspapers to the Black neighborhoods in Farmville,” Ghee said. He specifically mentioned delivering newspapers to families on Hill, Ely, South Main, Chambers, Madison, Redford, Franklin and Race Streets. “On Sunday mornings, my dad and I would deliver about 125 copies of the Richmond Times-Dispatch to the Black neighborhoods.”

“A far cry from what we see there now.”

Longwood Expands

By the time Ghee began delivering newspapers, the college had doubled in size since first using eminent domain in 1911. Longwood’s expansion facilitated rapid growth in student population often at the expense of the Black community. Ghee said he viewed Longwood as strictly for white people, as did most of the community.

Official Map of Farmville, 1934 (College Properties Marked as 'STC') / Courtesy of Krogh

“It was a white place,” he said. “Some of my clients who would get newspapers worked at Longwood. They might have been domestics in Longwood… I just think most people knew Longwood was for whites and didn't have anything else to do with it.”

According to a Farmville Herald article from May 3, 1949, “A picture of the rapid expansion of the college is indicated by the fact that she has sent out more graduates since 1940 than she did in all the previous years in her 77-year history,” the article read.

As the student population of Longwood grew, the demand for student housing and academic space grew with it. Jarman and Stevens Halls opened in 1951, Eason (then-Lancaster), Graham, Iler and Wheeler Halls in 1962, Cox Hall in 1963 and Stubbs Hall in 1966.

In 1958, Longwood College — which was still under the control of the State Board of Education at the time (who often worked on recommendations made by college administrators) — exercised its power of eminent domain for the third and fourth time in its history. In March, the college forcefully purchased land on Ely Street from Lucy D. Falwell and others.

In May 1958, Longwood exercised eminent domain once again — this time forcefully purchasing the parsonage of First Baptist Church, which is historically Black.

Longwood, after a six-year pause from exercising their power of eminent domain, would return to the practice in February 1964.

Elks Hall, where Stubbs Hall is now, was the Farmville Lodge for the Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks of the World, a fraternal organization for African-Americans. The land was initially acquired by the Trustees of the lodge in 1925 and was an important meeting place for the Black community in Farmville.

“Stubbs, that's where the Elks Hall was. That's where Black people had all of their dances and functions,” Reid said. “They had a meeting place, and then they would have dances and parties, the ‘bougie dances,’ like the formal dances back in the day.” Various articles from the Farmville Herald throughout the 1930s through 1950s mention Mardi Gras celebrations, beauty pageants, live music, dances and other events held at Elks Hall.

One year shy of what would have been its 40-year anniversary, Elks Hall was forcefully purchased by the college in 1964.

Digital Image of the Deed to Elks Hall

The college paid the Trustees of the lodge $17,500 in exchange for the property, according to the deed dated February 27, 1964. Also according to the deed, they were given until July 31, 1964 to leave the space. Eventually, the Elks Lodge relocated to its current location, near the former site of Mary E. Branch Elementary School.

A Farmville Herald article from 1965 mentions its demolition, in preparation for the construction of Stubbs on the corner. Stubbs would then open the following year.

Race Street Baptist Church

The forceful purchase of Elks Hall marked the beginning of a decade of aggressive expansion for Longwood College. In addition to Lancaster (now Eason), Graham, Iler, Wheeler, Cox and Stubbs, the college was preparing to build at least four new buildings — two as part of a ‘Fine Arts’ complex, and two high-rise dormitories.

University President Henry Willett shows students planned Fine Arts Complex / July 17, 1968 Issue of the Farmville Herald

In order to construct these buildings, officials at Longwood planned to expand further into the community down Pine Street, Race Street and the interconnecting streets. Race Street Baptist Church, so named for its location, was a historically Black church now known as Jericho Baptist Church.

Clara Johnson, a native of Prince Edward County who would later become Longwood’s first-ever Black administrative employee, has attended the church for her entire life. Born in 1948, she did not live in the “triangle,” but like Ghee, knew those who did very well.

“I knew the people that had to move,” she said. “It was close-knit, everybody knew everybody.”

Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, July 1910 (Mt. Zion Baptist Church identified in bottom left) / Courtesy of the Library of Congress

According to Johnson, and confirmed by property records, the church (then-named Mount Zion Baptist Church) was originally located near modern-day Hiner Hall. “[The original] was down where Hiner and Coyner are. [Longwood College] wanted to build a school there… I understand from reading that they swapped the land up on Race Street and then yielded that land over to Longwood for their school,” she said.

A deed dated January 14, 1914 detailed the transfer of property between the Trustees of Mt. Zion Baptist Church and B.M. Cox, relocating from the intersection of Madison Street and Pine Street to Race Street.

The congregation rebuilt and operated on that plot of land for half a century until Longwood once again expanded to the church’s doorstep.

During the intervening years, the church renamed itself the “Race Street Baptist Church,” with the first reference to the new name on August 9, 1918 in the Farmville Herald. According to various Farmville Herald articles over the decades, the church hosted concerts, community events and more for the Black community. Furthermore, the church served as a meeting spot for the Council of Colored Women and the local branch of the NAACP.

In 1967, Longwood College officials initiated condemnation proceedings against the church and ordered its demolition. According to the July 18, 1967 issue of the Farmville Herald, fifteen houses and various other structures were included in the same demolition request as the church, which cleared the way for Bedford, Wygal, Curry (Moss) and Frazer (Johns) Halls to be built.

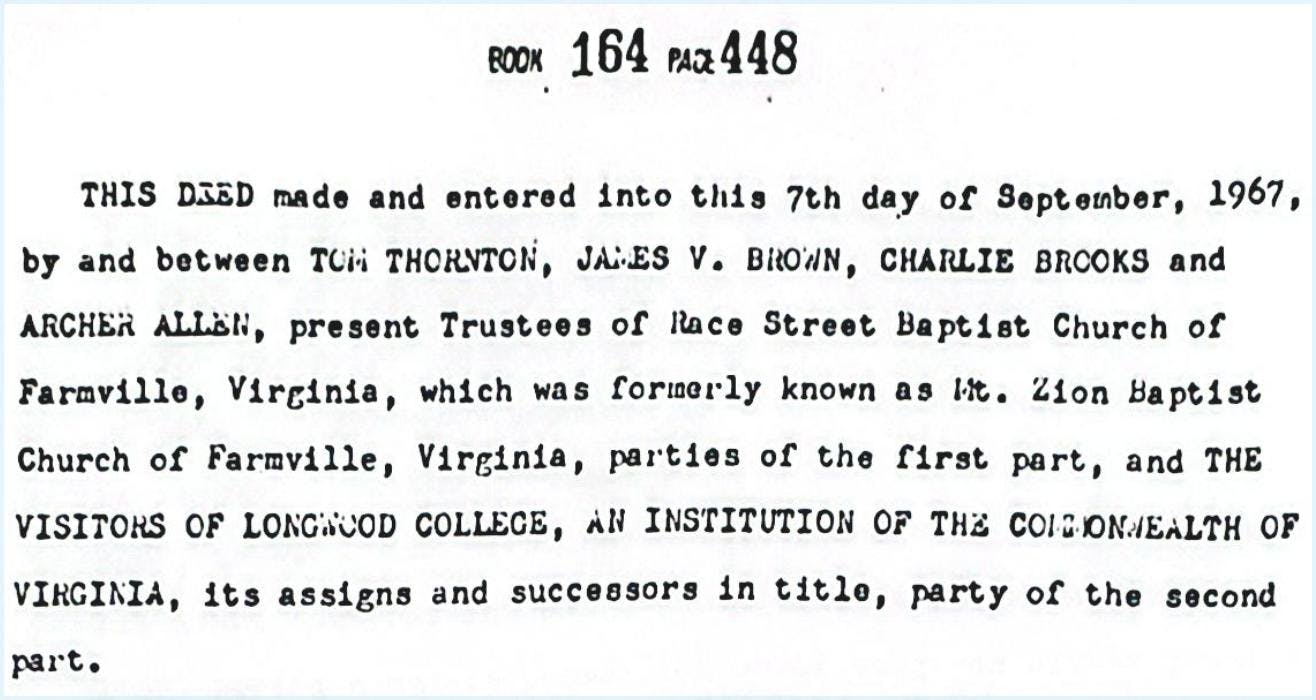

On September 7, 1967, the deed was agreed upon by Longwood College and the trustees of the church, which gave the church $18,000 in exchange for the property. The congregation was then given until September 12 to “[remove] from the premises… All pews, the drinking fountain, the bulletin boards, all light fixtures and all windows, and at which said September 12, 1967, period complete possession shall be given of the premises hereby conveyed to [Longwood College,]” the deed stated.

The building was torn down after September 13, when a public auction was held for removal of the structure and 21 others. “When we vacated that building, it was not dilapidated. As a matter of fact, it was a big church. It wasn't new, but it was a huge church,” Johnson said.

During the same period, parts of Race Street were removed in order to expand Stubbs Lawn. At the site of the former Race Street Baptist Church, the Greenwood Library stands today, roughly across from modern-day ARC Hall.

Soon after the forced relocation, the congregation built a new church on Franklin Street, where it stands today.

The Community Pushes Back

Map of Proposed Longwood Expansion, February 18, 1966 Issue of the Farmville Herald

People from the surrounding Black communities formed the “Committee of Concerned Citizens” to push back against Longwood’s expansion. They spoke at the August 2, 1966 meeting of the Board of Visitors, where they told the board that campus expansion had primarily impacted the Black community and questioned the nature of the expansion.

According to board minutes, the group told the board “that some of the Negro families had already moved once because of the expansion of the College and that there was no place for the families to go.”

A May 16, 1967 article from the Richmond Times-Dispatch, “Longwood Blames County Setup For Hiring Woes,” then-President Dr. James Newman blamed potential controversies over forcefully purchasing Black homes for delays in expansion and called the community a potential “powder keg.” Later that year, Governor Mills Godwin placed Newman on unrequested leave, and President Henry I. Willett Jr. soon took office.

Despite continued (but limited) expansion, Longwood College did not use eminent domain at any point between 1967 and 1990. However, the relationship between the Black community and the college worsened.

In 1985, Longwood College — then led by University President Janet D. Greenwood — released an interim master plan which was approved by the state on a provisional basis. The plan proposed further expansion into the surrounding community, which caused uproar from residents.

In part, the master plan sought to address one of the primary problems the college faced: a lack of parking.

In 1986, a town-hall-style meeting was held with residents and college officials, where community members and some local officials voiced concerns. Carl U. Eggleston, then a town councilor, told officials the plan “deviates around a lot of white property,” according to the November 26, 1986 issue of the Farmville Herald.

Front Page of the November 26, 1986 Issue of the Farmville Herald

According to the article, “The almost entirely Black audience listened to Don Lemish, the college’s vice president for institutional advancement, explain the position of the college administration, its board of visitors and the Virginia General Assembly regarding the process of acquiring new property for surface parking and resident housing.”

Furthermore, during the meeting, Lemish defended the practice. “Despite Eggleston’s charges of racial discrimination regarding the college’s master plan…” the article stated, “Lemish defended college procedures, saying they follow state requirements for expansion only within the [1985 master plan].”

Other members of the audience decried the expansion, one attendee told college officials, “How many whites have you displaced yet? I know none.” Another told them, “The Black community is being wiped out by the expansion of Longwood.”

In response to the proposed expansion, the community formed the “Committee To Save Our Neighborhood.” The group’s spokesperson was James Ghee, who had returned to Farmville in 1975.

At a meeting of the Board of Visitors on January 29, 1987, Ghee spoke to senior college officials, including Greenwood and Lemish.

James Ghee / Courtesy of the Democratic Party of Virginia

“We are fully cognizant of the fact Longwood College must expand,” he told them, according to the February 4, 1987 issue of the Farmville Herald. “We are not here to say we are opposed to expansion. But we are here saying we are opposed to expansion that drastically impacts on us as Black folks in that neighborhood and we do not have a chance to participate in the process leading to the decision.”

He also told the board, “We believe, and don’t want to believe, that the decision to proceed southwardly from Longwood’s present facilities is, as far as we can determine, a racially motivated activity. We’re not saying that you have purposely made a conscious decision based on race, but the impact, the impact, the effect gives a clear appearance of a racial decision.”

In response, one board member pushed back on this assertion, but eventually admitted racial motivation “seems to be the superficial appearance of it.”

At the meeting, the Board of Visitors formed a committee of university officials and community members to advise them on potential expansion. However, at the Board’s September meeting, they voted against both of the committee’s recommendations, one of which was to halt the practice of eminent domain.

“Opting not to accept the recommendation from two of its own committees, the Longwood College Board of Visitors voted Saturday to use eminent domain, if it feels it must, to build a parking lot on the block of Main, Hooper, Franklin, and Pine,” according to an article from the September 16, 1987 issue of the Farmville Herald.

According to the Board minutes from the September 12 meeting, the third action of the motion approved by the Board stated, “A parking lot [shall] be developed within the area bounded by Pine, Hooper, Franklin, and Main Streets; to which end the College should promptly make every reasonable attempt to purchase at fair market price such property within this area as it does not presently own, but that, should such negotiations fail and as a last resort, the Board of Visitors on separate action should request the State to exercise its right of eminent domain to obtain those properties…”

The board added, “This is with the understanding that these properties which are owner-occupied will be given the opportunity at their sole discretion to remain on the property for their lifetime.”

This move was in opposition to the advisory committee, as was the decision to not build parking in Bicentennial Park (located at the intersection of Buffalo, Randolph and High Streets), an act to preserve the park later demolished in order to build Radcliff Hall.

Rev. Nelson W. Jordan / Courtesy of the National Museum of African American History and Culture

Once again, in 1990, the community pushed back against proposed expansion on Franklin Street. According to Ghee, at 311 Franklin Street was a house with great significance to Farmville’s Black community.

“There was a house on the corner of Franklin and Pine that had been Jordan's home place,” Ghee said. “And out of that Jordan home place had come some outstanding Prince Edwardians.”

The Jordan family first settled in Farmville in the late 1800s, when Rev. Nelson Jordan moved there following his education in Richmond. Born and enslaved in Albemarle County, VA, Jordan fought in the Union Army in Mississippi, Tennessee and Louisiana. Part of the 55th Regiment Infantry of the U.S. Colored Troops, he returned to Virginia after the war.

Jordan’s daughter Mozella Jordan Price served as supervisor of Appomattox County Negro Schools from 1919 until 1963. Price was a trailblazer for the education of Black children in Appomattox — helping establish a Rosenwald School in 1928 and eventually helping found the county’s first Black high school.

Mozella Jordan Price / Courtesy of the Carver-Price Legacy Museum

During the school closures in Prince Edward County, many Black students seeking an education travelled to Appomattox County for schooling. Students without relatives in Appomattox were offered a place to stay at her home, named Winonah Camp, which also served as an interim elementary school for Black children. While Mozella J. Price died in 1971, her story lives on at the Carver-Price Legacy Museum in Appomattox.

By 1990, none of Rev. Jordan’s descendants lived in the house on Franklin Street and Longwood pursued ownership of the property. On March 16, 1990, Longwood used eminent domain to forcefully purchase the house. After a brief legal battle over “just compensation,” in which Ghee was one of the attorneys representing the family, Longwood was ordered to pay Jordan’s descendants $20,000 for the property. The house was demolished soon after.

“We had wanted to do something to memorialize what had come out of that house,” Ghee said. “They told us, ‘Get the hell out of here. We’re taking it, that’s part of our master plan.’”

The land where the house stood is now a parking lot.

Longwood Ends Eminent Domain Use

Later that year, Longwood used eminent domain for the final time to forcefully purchase property from Lester Andrews Jr., who owned property on Griffin, Redford and South Streets. Officials at Longwood negotiated with Andrews for several months before deciding to exercise their power of eminent domain, and Andrews was given $98,000 in exchange for the property.

Longwood unsuccessfully attempted to use eminent domain in the mid-1990s after a showdown with Prince Edward County to acquire lands within the triangle. The college wanted to purchase the “playing fields” of Moton in order to build athletic facilities on the property, but Prince Edward County would not sell the land for less than $700,000, which Longwood officials thought was too expensive.

Longwood requested for the state to allow them to use eminent domain for the property, but the request was denied by the administration of Governor George Allen, who told the college to negotiate. Eventually, Longwood and Prince Edward struck a deal without the use of eminent domain.

The year following the agreement, Dr. Patricia Cormier took office as Longwood’s president.

According to Ghee, after Cormier began her tenure as president, the community approached the college once again on the issue of eminent domain.

“When Cormier came, the local branch of the NAACP and the citizens group met with her, and she said, ‘Okay, we aren’t going to use eminent domain. We're going to wait for people to say they're willing to sell to us,’” he said.

Ghee said, “That’s when the threat of eminent domain stopped.” He later added, “But by that time, the community had been desecrated.”

Since then, officials at Longwood have kept their word on stopping the usage of eminent domain. According to Ghee, Longwood changed their plans for the Health and Fitness Center due to one woman’s refusal to sell her house on Hooper Street. Longwood did not purchase the house until after her death, and the house still stands today.

Longwood Apologizes

In the years since, Longwood’s relationship with the community has grown stronger as the university apologizes for its actions during the 20th century.

The Board of Visitors passed a resolution in 2014, during the second year of Reveley’s administration, which expressed regret for the negative impact on the Black community. The resolution states, "Longwood caused real and lasting offense and pain to our community with its use of eminent domain to facilitate campus expansion, and acted with particular insensitivity with regard to the relocation of a house of worship.”

Johnson, still a congregant at Jericho Baptist Church (formerly Race Street), began working at Longwood College in 1978.

Growing up, she viewed Longwood far differently than she does now. “I viewed Longwood as a place that we couldn't hang around,” she said, “And we were always on, ‘You can't linger around, don’t cross the lawn or anything’… I don't say scary, but it was almost scary to me growing up, because you hear terrible things.”

In an interview with Longwood students published by the Moton Museum in 2018, part of a collection titled ‘All Eyes on Prince Edward County,’ she said, “It was an unspoken decree. Don’t be around Longwood if you’re Black, especially in the evening.”

Johnson met numerous challenges at a predominantly white institution as the first Black administrative employee.

Clara Johnson / Courtesy of Jericho Baptist Church

“Getting in there, I realized I knew I had to do things at the employment office, that after these women became my friends there, I realized they didn't have to,” she said in her interview with The Rotunda. “When I went there, being the only Black that ever sat in office there, I met some challenges, and that's the way people are.”

According to the 2018 publication, “Some co-workers shunned her and made it difficult to succeed. Acceptance wasn’t something that was going to come easily. The few co-workers who risked their reputations to be friendly are some of her closest friends.”

Despite her challenges, after working there for over three decades, she remembers her time at Longwood fondly. Johnson said to The Rotunda, “On the other hand, there were some really, really nice people, good people. One of the girls that I started working with… she's my friend now.”

Johnson gave 32 years to Longwood before retiring in 2010.

She said she believes Longwood’s relationship with the community has grown significantly over the years. “I think things are progressing more to where they should be,” she said.

Similarly, Ghee said the relationship is more positive than it once was. “Clearly, one would have to say it's more positive, because we see the community using the facilities more,” Ghee said.

“Before the YMCA came to town, in summer Longwood had a swimming program at the pool that everybody was able to participate in. It appeared to have been an effort on their part to say, ‘I want to be in a different posture now than I was in the 60s.’ I would [also] think that the enrollment sort of shows that, and the faculty and administration sort of shows that,” Ghee said.

Moving Toward Atonement

In early 2024, the Virginia General Assembly established the Commission to Study the History of the Uprooting of Black Communities by Public Institutions of Higher Education in the Commonwealth. According to the 2024 State Budget, the commission will “determine (i) whether any public institution of higher education has purchased, expropriated, or otherwise taken possession of property owned by any individual or entity within the boundaries of a community in which a majority of the residents are Black in order to establish or expand the institution's campus and (ii) whether and what form of compensation or relief would be appropriate.”

Chaired by Richmond Delegate Rev. Delores McQuinn, the commission held its first meeting in August 2024. The commission, split into four subcommittees to address various parts of the commission’s work plans, seeks to have a recommendation finalized by November 2025.

Each public institution of higher education in Virginia was asked to provide a letter addressing several questions from the commission, which Reveley replied to on January 15, 2025. In his letter, Reveley reflected on Longwood’s “regrettable chapters” of eminent domain usage, and said the institution has taken steps to atone for those chapters.

“Successive presidents and Boards of Visitors have taken concrete steps to repair the relationship with the community that was affected by the use of eminent domain and to capture, preserve, and study the history that we share so that we may work more effectively for the betterment and progress of the entire Farmville community,” Reveley wrote.

The letter details the 11 times Longwood officials used the practice to forcefully purchase land, as well as discusses specific examples of the steps Longwood has taken to rebuild their relationship with the surrounding community.

One of the questions from the commission was, “Is there any indication that the properties acquired were from a community in which the majority of residents were Black?” Reveley, as part of a longer answer, wrote, “Longwood used the threat of eminent domain to negotiate property acquisitions with both white and Black citizens.” He also emphasized, “The neighborhoods around campus and in the triangle were not strictly segregated.”

According to an email statement from University Spokesperson and Deputy to the President Matt McWilliams, research for the letter was done by Reveley, Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs Dr. Larissa Smith and himself. Furthermore, Reveley noted research is ongoing into Longwood’s usage of eminent domain as part of the 2039 Bicentennial Initiative.

When asked via email if they contacted or spoke with any members of the impacted community while writing the letter, McWilliams replied, “We have been doing that work for many years now, and those many conversations especially over the last 12 years certainly informed the University’s response. As noted in the letter, work continues through Longwood’s Bicentennial Initiative to research specific activities and decisions made in the University’s history that affected these communities.”

Ghee, president of the Prince Edward County NAACP who has served at the local, state and national levels of the group, said he had not been contacted and did not know of anyone who had been contacted.

Asked if he wished a representative from Longwood would have contacted him to take part, Ghee said, “No, because I would not have wanted to be a part of what appears to be a sugar-coating of what actually happened.”

This is the second of a series of articles by The Rotunda chronicling the college’s use of eminent domain and its impact on the local community. The Rotunda’s Editorial Board encourages people willing to share their stories or provide information to contact the staff at therotunda@live.longwood.edu.