The new obelisk stands at 16 feet tall, 10 feet shorter than the confederate statue right across the street.

During Convocation 2017, Longwood University President W. Taylor Reveley IV announced a new idea to create a monument representing the Farmville community’s role in both the Civil War and the Civil Rights movement.

Reveley’s announcement came in light of the national controversies surrounding the continued existence of Confederate monuments, prompting a public conversation about Richmond’s Monument Avenue.

After roughly a year of planning and constructing, the new monument was revealed on Sept. 14. The monument, an obelisk that stands at 16 feet tall, is positioned across from Ruffner Hall and next to the Confederate statue along High Street facing campus.

“We haven’t always celebrated our history, which has seen more than its share of pain and injustice,” said Reveley in a Sept. 7 open invitation posted on Longwood's website. “ … it is remarkable how many people in and around this community, in the face of difficult odds, have been front and center in the fight to expand our nation’s ideals of liberty.”

The obelisk stands 10 feet shorter than the statue next to it, also signifying that it might be more insignificant in history. The Civil War is a major part of our country’s history, but is it really bigger than the societal advances we’ve made to end discrimination?

On Aug. 11-12, 2017, white nationalists seized Charlottesville in response to the city taking down the Robert E. Lee statue in Emancipation Park. The “Unite the Right” rally was organized by Jason Kessler and Richard Spencer, two publicly-known white supremacists and political extremists.

The rally sparked a huge national debate around whether or not Confederate statues should be torn down or removed. The town of Farmville did not give a direct statement on the 26-foot tall Confederate monument that was erected on Oct. 11, 1900 in reference to the Charlottesville rally.

The Civil War went though Farmville, with its last major battle occurring near Sayler’s Creek, according to Farmville Area Chamber of Commerce. Robert E. Lee retreated through the town and the Confederates attempted to burn down the 120-foot-tall High Bridge that’s nearly half-mile-long span across the Appomattox River.

Farmville was the subject of the Confederate Army's desperate effort to get rations to feed its soldiers near the end of the war.

Farmville and Prince Edward County also have deep involvement with the Civil Rights Movement, igniting the social change from segregation to integration.

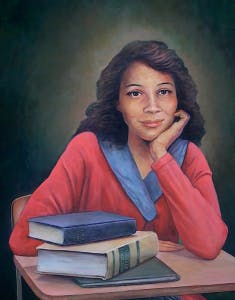

In 1951, 16-year-old Barbara Johns walked out of class to protest the conditions of R. R. Moton High School, a primarily African American school. The conditions were extremely inferior compared to those at Farmville High School, the all-white school nearby.

A portrait of Barbara Johns, the student who led the strike against the inferior conditions of R. R. Moton High School

“We held two or three classes in the auditorium most of the time, one on the stage and two in the back,” former R. R. Moton principal M. Boyd Jones told journalist Bob Smith in 1961. “We even held some classes in a bus.”

According to Farmville’s official website, the strike helped start the desegregation movement in America that led to Brown v. Board of Education.

White residents had mixed feelings and reactions. John Watson, a committee member for the strike, later learned that some white people supported the movement.

However, they feared retribution by segregationist leaders and feared threats to their jobs and businesses. When it was clear the black community planned to sustain a serious civil rights campaign, white leaders began a campaign on the grounds of economic and social intimidation.

Despite all of this, there was an absence of violence in the county, which all residents should be proud of to this day.

Three days after Johns got other students on board with the strike, Virginia NAACP Executive Secretary Lester Banks met with the students of R. R. Moton and their parents to tell them the NAACP wanted to take on their case to end segregation. Roughly a month later, the NAACP filed Davis, et al. v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, in federal court to challenge the idea that segregation in Prince Edward County schools was unconstitutional.

Moton student plaintiffs pictured in 1953.

In Dec. 1952, the Supreme Court started hearings for Brown v. Board of Education which is five different cases in the U.S. combined, including the case in Prince Edward County. Two years later, the Supreme Court ruled segregation in schools unconstitutional, but left out how to manage the segregation issue.

Five years post-court ruling, Prince Edward County Board of Supervisors decided to stop funding schools for the 1959-60 academic year to prevent integration. However, the schools were closed for five years.

On March 28, 1962, Martin Luther King Jr. visited Prince Edward County, and a year after on March 18, 1963 U.S. attorney general Robert F. Kennedy said during a speech, “the only places on earth not to provide free public education are Communist China, North Vietnam, Sarawak, Singapore, British Honduras—and Prince Edward County, Virginia.”

After the county’s public schools had been closed for five years, the Supreme Court in Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County ruled the county had violated the students’ rights to education and ordered the schools to reopen.

On April 23, 2001, R. R. Moton High School was reopened as the Robert Russa Moton Museum for the study of civil rights in education on the fiftieth anniversary of the school strike.

The story this monument represents prompts a simple question: is it effective in highlighting a crucial part of not only Farmville’s history, but America’s history?

The obelisk is a step in the right direction for Farmville and Prince Edward County. While it sits next to a Confederate statue, it symbolizes the steps that were taken to move America forward.

However, I believe it would’ve been genuinely more powerful to replace the Confederate statue with the obelisk - that would’ve shown Farmville digging deeper to praise an end to segregation and not promoting racist history.

It’s important to understand that racism was a huge factor in both the Civil War and the Civil Rights Movement - but that doesn’t mean we should praise it. The Confederate statue represents the soldiers who fought on the side of slavery, leading to prejudice for decades to come.

Prince Edward County is a predominantly white area with only 33.1 percent of African American residents, according to the United States census. To highlight the successes of that community while also shedding light on the Confederacy doesn’t make sense.

The long-term effects of discrimination are still present, which is why it’s important to document them and highlight the attempts to end prejudice as a whole. Confederate monuments don’t do that.

However, the “new birth of freedom” the obelisk provides moves the county in the right direction of focusing on the history that makes it unique. Our two-college town has been at the center of a lot of important history, and this monument re-establishes that fact.

Editor's note: The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.